Public Art In London – Most Famous Installations

Public art in London encompasses a wide range of artistic expressions displayed in public spaces — statues, memorials, murals, street art, and installations. These works are deeply woven into the city’s streets and everyday life, becoming part of the rhythm of movement, reflection, and interaction.

From the poetic “A Conversation with Oscar Wilde” to the playful “Click Your Heels Together Three Times” in Canary Wharf, these installations add layers of meaning to London’s urban environment. Other notable examples include “Knife Edge Two Piece”, “Winged Figure”, “Nelson’s Ship in a Bottle”, “ArcelorMittal Orbit”, “Quantum Cloud”, “Traffic Light Tree”, David Bowie Mural in Brixton, and the Cable Street Mural in East London.

What makes London’s public art unique is its accessibility — it democratizes art, bringing it out of galleries and into the open where everyone can engage with it. Projects are funded by government bodies, private developers, cultural institutions, or emerge from grassroots efforts, each adding different voices to the cityscape.

Art agencies also play a key role in shaping London’s public art scene by supporting and promoting installations that communicate London’s character, foster a sense of belonging, encourage social dialogue, and ultimately shape the city’s dynamic and inclusive identity.

A Conversation with Oscar Wilde

A Conversation with Oscar Wilde is a public sculpture by Maggi Hambling located on Adelaide Street in central London, unveiled in 1998.

This distinctive installation serves as a tribute to the celebrated playwright and wit. Rather than opting for a traditional statue, Hambling created an interactive piece resembling a granite bench shaped like a sarcophagus. From its upper end, a bronze bust of Wilde emerges, his hand raised and holding a cigarette as if in mid-conversation with passersby.

The bench is polished green granite, while the bust is cast in bronze. One of Wilde’s famous quotes from Lady Windermere’s Fan is engraved along the bench’s edge:

“We are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars.”

Its placement near Charing Cross Station encourages public engagement, inviting people to sit, reflect, or even “converse” with the iconic writer — perfectly in line with Wilde’s enduring legacy as a provocateur of thought and humor.

Knife Edge Two Piece

Knife Edge Two Piece is a public sculpture by Henry Moore, located outside the Houses of Parliament in London, created between 1962 and 1965.

This striking bronze artwork is one of Moore’s most recognizable large-scale public installations. The piece is composed of two separate but interrelated forms, measuring approximately 275 cm in height and 366 cm in width (108 x 144 inches).

The sculpture features a sharp, blade-like edge, inspired by the natural contours of bird bones — an organic influence central to much of Moore’s work. The two-part composition is carefully arranged to create a deliberate spatial tension. The gap between the pieces isn’t space — it frames the environment, connecting the sculpture to its urban setting and inviting viewers to consider their position about it.

Despite its monumentality, the sculpture maintains an approachable, almost meditative presence. Cast in bronze, its surface bears the subtle textures and patina that emphasize its tactile quality and timelessness.

Knife Edge Two Piece exemplifies Moore’s philosophy of integrating art with public space — transforming a busy area near Westminster into a site for quiet reflection through abstract form and material weight.

Winged Figure

Winged Figure is a public sculpture by Barbara Hepworth, installed on the side of the John Lewis department store on Oxford Street, London, in 1963.

This iconic piece brings abstract modernism into the heart of one of London’s busiest commercial districts. Standing at 5.8 meters (19 feet) tall, the sculpture features two asymmetric, wing-like forms rising vertically from a base, subtly bending toward one another. The forms are joined by a series of radial stainless steel rods that create a sense of tension and unity, almost as if the wings are held together by invisible forces.

Made primarily from aluminum, with steel rods providing structural and visual contrast, Winged Figure is a striking example of Hepworth’s ability to blend geometric abstraction with an organic, almost spiritual sense of motion and balance.

Commissioned by John Lewis in the early 1960s, the piece was designed to reflect the company’s ideals of common purpose and progress.

Today, it remains one of London’s most recognized and photographed public sculptures, seamlessly integrated into the urban landscape while inviting moments of reflection high above street level.

Nelson’s Ship in a Bottle

Nelson’s Ship in a Bottle is a public art installation by Yinka Shonibare CBE, originally unveiled on the Fourth Plinth in Trafalgar Square, London, in 2010.

The sculpture is a 1:30 scale replica of HMS Victory, Admiral Lord Nelson’s flagship during the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. Enclosed within a giant glass bottle, the model features 37 vibrant sails made from richly patterned textiles inspired by West African designs—a signature material in Shonibare’s work.

Measuring approximately 4.7 meters in length and 2.8 meters in height, the bottle rests atop a wooden plinth, offering a playful yet powerful contrast to the neoclassical surroundings of its original display site.

While visually striking, the artwork carries deep cultural and political meaning. It reflects on themes of British naval history, colonial expansion, and the global legacy of empire, while celebrating contemporary Britain’s multicultural fabric.

The use of African textiles inside a quintessentially British symbol challenges traditional narratives and invites viewers to reconsider the stories tied to national monuments.

After its time on the Fourth Plinth, the sculpture was relocated and now has a permanent home outside the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich. As the first Fourth Plinth commission by a Black British artist, Nelson’s Ship in a Bottlemarked a significant moment in public art, bringing historical reflection and cultural identity into the center of public discourse.

ArcelorMittal Orbit

The ArcelorMittal Orbit is a monumental public sculpture and observation tower designed by Anish Kapoor and Cecil Balmond, located in Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park in Stratford, London.

It is 114.5 meters tall and the largest piece of public art in the United Kingdom. It was unveiled as part of the 2012 London Olympic Games. The structure combines sculpture, engineering, and architecture in a spiraling form made from 560 meters of red tubular steel, creating a striking visual landmark visible across East London.

Positioned between the London Stadium and the Aquatics Centre, the Orbit features two indoor observation platforms that offer sweeping views of the Olympic Park and the wider London skyline. At its base sits a visitor pavilion, and since 2016, the structure has also incorporated the world’s longest tunnel slide, designed by Carsten Höller, adding a playful interactive element to the experience.

Beyond its dramatic design, the Orbit carries symbolic weight — it was commissioned to represent regeneration and progress in East London, serving as a lasting legacy of the Olympic Games. Its looping, unstable-looking form was intentionally designed to challenge conventional ideas of beauty and monumentality, inviting public interpretation and engagement.

Today, the ArcelorMittal Orbit stands as a bold fusion of art and infrastructure, drawing visitors with its unique form, expansive views, and status as a contemporary icon of London’s transformed eastern skyline.

Quantum Cloud

The Quantum Cloud is a large-scale public sculpture by British artist Antony Gormley near the O2 Arena on the River Thames in London.

Standing at 30 meters (98 feet) tall, the “Quantum Cloud” is Gormley’s tallest creation and was commissioned for the millennium celebrations in 1999. The sculpture is constructed from steel and consists of a collection of tetrahedral units made from 1.5-meter-long steel sections.

These units are arranged to create a dynamic, cloud-like form that vibrates with energy, symbolizing the concept of quantum uncertainty and the unseen forces that shape the world around us.

The central figure within the sculpture evokes a human form. At the same time, the outer tendrils and irregular structure suggest the chaotic nature of quantum physics, inspired by chaos theory and fractal growth. Gormley’s design is influenced by the ideas of quantum physicist Basil Hiley, particularly the notion of “algebra as the relationship of relationships,” suggesting that human presence can transcend physical form.

Situated on a cast iron platform in the river, the sculpture is both a striking visual landmark and a philosophical reflection on the intersection of the human body with the external, unseen world.

Today, Quantum Cloud stands as a testament to Gormley’s exploration of the body, perception, and the vastness of the universe, inviting visitors to consider their relationship with space and presence.

Traffic Light Tree

The Traffic Light Tree is a public sculpture by French artist Pierre Vivant in London, England, designed to capture the dynamic and restless energy of the Canary Wharf financial district.

Standing at 8 meters tall, the sculpture comprises 75 sets of computer-controlled traffic lights arranged in a tree-like form. Situated on a traffic roundabout near Billingsgate Market, close to Canary Wharf, the piece is a striking urban installation that contrasts the usual rhythms of nature.

Unlike the predictable cycles of a tree’s growth, the lights in the Traffic Light Tree change in irregular patterns, reflecting the relentless pace and energy of the nearby financial hub.

Originally placed on a roundabout in Millwall in 1998, it was relocated to its current position in 2011, continuing to engage viewers with its vibrant and chaotic light displays. The design is inspired by London plane trees, which are common in the area, and was originally intended to reflect the activity of the London Stock Exchange.

However, due to the high costs of such an implementation, the lights instead focus on the overall restlessness of the surrounding district.

Despite initial confusion from motorists unfamiliar with its purpose, the Traffic Light Tree has become a popular fixture, admired by both locals and tourists for its unique commentary on urban life and the passage of time.

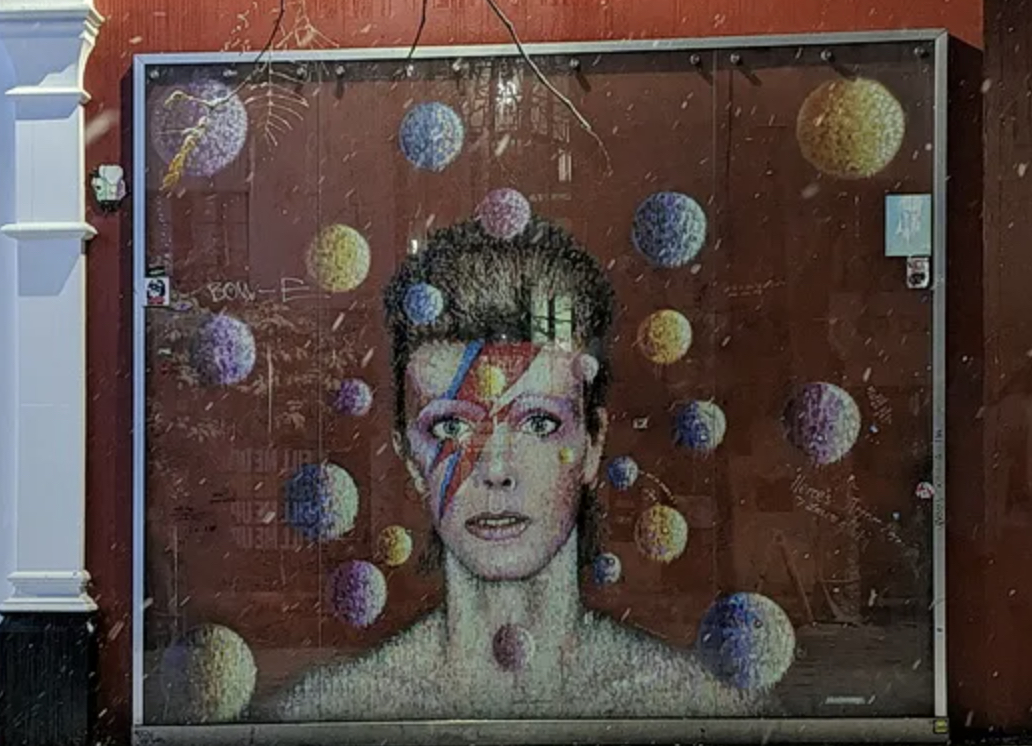

David Bowie Mural, Brixton

The David Bowie mural in Brixton, London, is a large-scale public art piece that pays tribute to the legendary musician, located on the side of Morleys department store on Tunstall Road.

Painted in 2013 by Australian street artist Jimmy C, the mural features Bowie in his iconic Ziggy Stardust persona from the cover of his 1973 album Aladdin Sane. The artwork, vibrant and striking, stands as a powerful tribute to Bowie’s legacy.

The mural, not only an artistic depiction, became a shrine for fans after Bowie’s death in 2016, with many leaving flowers, notes, and personal tributes in front of it.

The mural is located on the very building where Bowie was born, adding a layer of personal connection to the piece. Recognized for its cultural significance, the mural has been granted a local listing to protect it, and discussions have been raised about renaming the area or creating a permanent memorial for Bowie.

The David Bowie mural remains an enduring symbol of the artist’s influence and his deep connection with his fans, particularly in the community of Brixton.

Cable Street Mural, East London

The Cable Street Mural is a large-scale public art piece in East London commemorates the 1936 Battle of Cable Street, a historic event in the fight against fascism.

Located on the side of St George’s Town Hall in Shadwell, the mural was completed in 1983 and vividly depicts the confrontation between residents and the police, who were protecting a march organized by the British Union of Fascists. This artwork is a collective creation, with contributions from artists such as Dave Binnington, Paul Butler, Ray Walker, and Desmond Rochfort.

The mural is characterized by its bold and dramatic use of color, illustrating powerful scenes from the battle, including the erection of barricades, throwing objects at police, and the overall community resistance against the fascist march. It’s an expressive reminder of the unity and resilience of the local people in the face of oppression.

The Cable Street Mural stands as a significant cultural and historical landmark, honoring the legacy of those who fought for freedom and equality. It continues to inspire and remind viewers of the ongoing struggle against fascism.

Click Your Heels Together Three Times, Canary Wharf

Click Your Heels Together Three Times is a permanent, large-scale public art installation by LGBTQ+ artist Adam Nathaniel Furman, located at Adams Plaza Bridge in Canary Wharf, London.

The artwork is inspired by the iconic ruby shoes from The Wizard of Oz and serves as an architectural-scale equivalent, celebrating the journey of self-discovery and the importance of embracing one’s true identity and desires.

The installation wraps around the underside and pillars of the bridge, creating a colorful and visually striking experience for visitors.

Adam Nathaniel Furman, renowned for using color and pattern to create queer spaces in the public realm, designed this piece to reflect themes of transformation and inclusivity. It forms part of the Canary Wharf Group’s public art collection, one of the largest free-to-visit outdoor collections in the UK.

This bold and vibrant installation offers a welcoming and inclusive statement, enhancing the public space while inviting visitors to reflect on the power of self-expression.

What Is the Role of Public Art in Shaping London’s Identity?

The role of public art in shaping London’s identity is significant, as it communicates the city’s character, fosters a sense of belonging, promotes social dialogue, and enhances urban spaces. Public art reflects the diversity of London’s communities and plays a crucial role in creating a dynamic, inclusive urban environment.

- Communication of Identity. In London, public art reflects the city’s cultural and historical significance, shaping its identity. Iconic sculptures and street art create recognizable landmarks, fostering pride and belonging. These works contribute to the city’s evolving character, resonating with both residents and visitors.

- Cultural Expression. As a platform for cultural expression, public art allows London’s diverse communities to showcase their values and experiences. It visually represents the city’s ongoing cultural evolution, offering an inclusive space for individuals to share their unique perspectives and stories.

- Social Dialogue and Engagement. Through art, social, political, and environmental issues come to the forefront, inviting dialogue and reflection. These works challenge viewers to think critically, transforming urban spaces into active sites for communal engagement and connecting people through shared cultural experiences.

- Top-Down and Bottom-Up Approaches. Public art in London arises from both top-down governmental initiatives and bottom-up community-driven projects. While large-scale, iconic works are often government-funded, local grassroots efforts ensure art reflects community values, creating a diverse and dynamic artistic landscape across the city.

- Enhancing Spaces. Art breathes life into urban environments, transforming everyday spaces into vibrant, engaging locations. By adding color and meaning, these pieces revitalize parks, streets, and squares, encouraging exploration and interaction while fostering a sense of community and belonging in public spaces.

- Catalyst for Change. Art can catalyze social change by highlighting critical issues like inequality and environmental concerns. It challenges societal norms and sparks meaningful public discourse, shaping the city’s social and political landscape, and motivating reflection, action, and dialogue within the community.

As seen in projects supported by agencies like MTArt, public art actively contributes to London’s identity by supporting artists who bring new and meaningful dialogues into public spaces. These collaborations allow for art that goes beyond decoration, fostering inclusivity and engagement in the city’s evolving cultural landscape.